Information about Armenia and Armenian culture is scarce in state-approved English textbooks. Considering the fact that, in recent years, Armenian students have increasingly preferred textbooks published by Oxford and Cambridge Universities as well as Macmillan, where such information is entirely absent, the relevance and urgency of the issue become clear. For objective reasons, the Armenian school student is unable to adequately present Armenian culture in English—an ability that is rightly included in the educational standards for foreign languages.

It was precisely this problem that our learning project with 11th-grade students aimed to address.

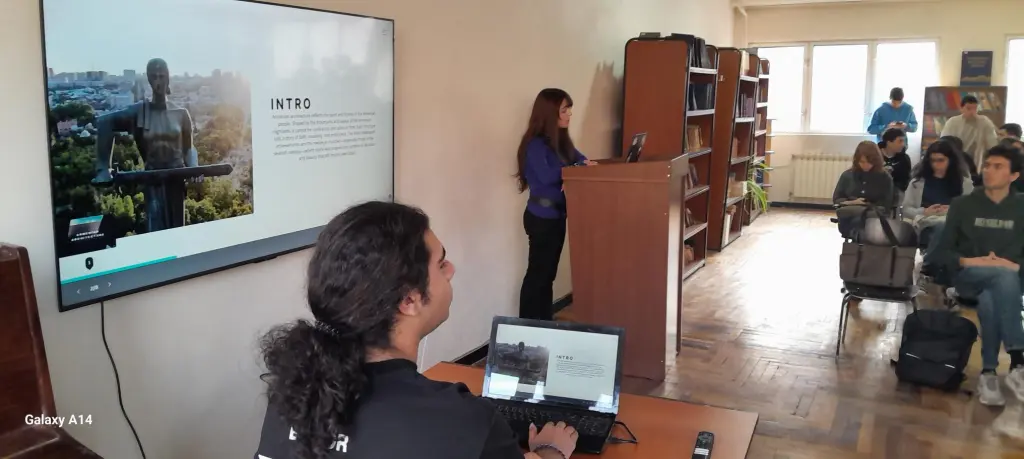

The first step toward solving the issue was the public presentation of the project on November 21 in the Reading Hall of the Research Lyceum, attended by about 60–70 students. The first speaker was Irina Grigoryan, whose topic focused on Armenian architecture. She presented both the architectural features of historical monuments—particularly ecclesiastical architecture—and aspects of modern urban design. Armenian architecture reflects the spirit and history of the Armenian people. Shaped by the mountains and valleys of the Armenian Highland, it cannot be confined to a single place or era. Each structure tells a story of the Armenian people’s faith, creativity, and resilience.

While speaking about modern architecture, Irina highlighted the significant contributions of Alexander Tamanian.

A short research project on Armenian carpet weaving was presented by Anna Yeghoyan. She provided information about the oldest Armenian carpets, compared the characteristics of Armenian and Persian carpets, and explained how to distinguish them. The primary motif of the Armenian carpet is the cross, while Persian carpets do not feature it.

In her presentation, Anna also spoke about Megeryan handmade carpets, Tufenkian carpets, and the Vaslyan antique carpet gallery.

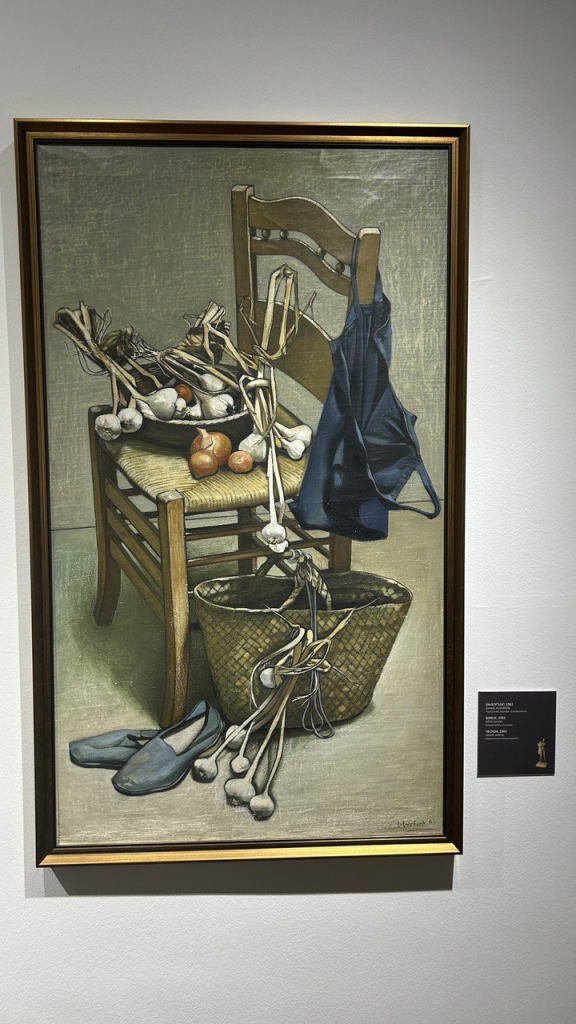

The theme of Armenian fine arts was presented by Sargis Sargsyan

If Saryan—then bright wildflowers and sun-kissed fruits in a cheerful still life.

If Hakobyan—then a bunch of garlic casually thrown on a chair in a modest kitchen corner.

If Saryan—then an August grapevine heavy with sweet, sunlit clusters.

If Hakobyan—then a vineyard pruned for winter in the bleak days of December.

If Saryan—then a proud portrait of Aram Khachaturian, the composer of Spartacus and Gayane ballets.

If Hakobyan—then a thin, weary man bent under the sorrow of the world, seated on a backless wooden stool.

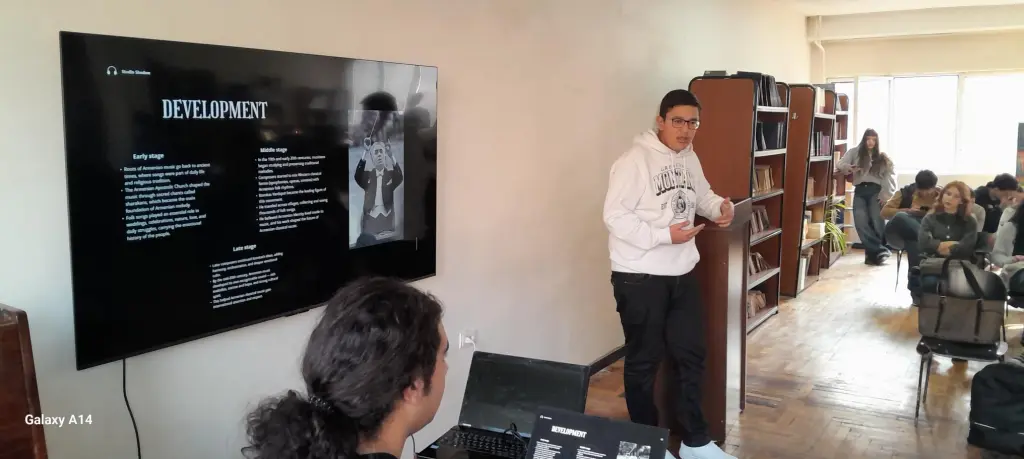

A wonderful presentation on Armenian classical music was delivered by Gurgen Abrahamyan, whose speech was accompanied throughout by carefully selected background music.

The haunting sound of Krunk played as he spoke about Komitas. The exhilarating Sabre Dance by Aram Khachaturian accompanied Gurgen’s brief account of the great composer’s life and work. His musical choices were remarkably tasteful. For instance, when the slide dedicated to Arno Babajanyan appeared, the hall heard his Nocturne performed on piano. The next slide was devoted to Tigran Mansuryan, accompanied by the tender, soul-soothing music written for the film A Piece of Sky (Կտոր մը երկինք).

The project concluded with the final presentation by David Malkhasyan, dedicated to Yeghishe Charents. Within his remaining five minutes, David could not cover everything he had prepared. Therefore, he chose to focus not on Charents the poet with his brilliant works, but on Charents the person—restless, quick-tempered, loud, a man who once shot at the 17-year-old girl who rejected him, a man who struggled with addiction. David’s choice is understandable: he envisions his future in the field of history, and historians are always inclined to uncover the darker, lesser-known pages of our past.